WHY SO… CURIOUS?

We named our blog after it, we're trying to live by it for a year, but what actually is it? We can't really assert that we are curious, without first being curious about curiosity (now say that 5 times quickly...).

So strong is our drive to obtain information that human beings are sometimes referred to as informavores (someone please get that on a tee-shirt). We consistently strive to find out about stuff, learn more, explore more, question everything. But if ignorance is bliss, why are we so intrigued?

THE BEGINNING

Ohh Evolution, you always seem a sensible place to start and this is no exception.

The evolutionary benefit of seeking out new information, especially in nature, is a pretty good explanation behind inquisitive behaviour. Exploration allowed more beneficial food sources to be identified, better and safer environments to be discovered and more resources to be found. Those animals who wandered further from the nest would have had an advantage when it came to living long enough to make lots of animal babies.

But then why, in the mind of a (relatively) evolved human, is the gathering of information still so compelling? When the threat of starvation and/or competition is largely addressed (once you are married, with children, and can stock a fridge) your desire to learn (and get distracted) doesn't seem to just just...fizzle out. What keeps us going?

Well, based on the research of some (rather curious) scientists, it's been suggested that the above evolutionary pressures have made information seeking intrinsically rewarding. In other words it makes us feel good.

all of the feels

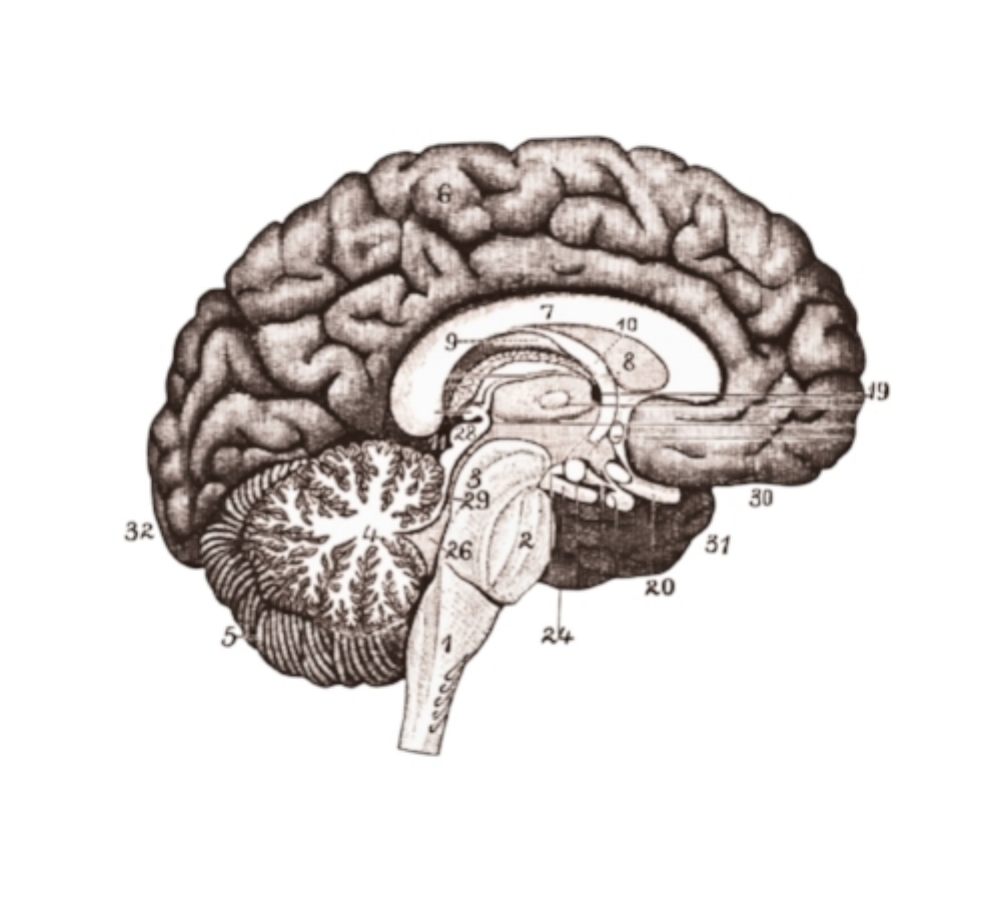

In a 2014 a group psychologists at the University of California ran a study on 19 volunteers. They monitored their brain activity with an MRI scanner whilst asking participants to review a set of random questions. When they were asked to determine which answer they'd be most curious to know (like "what does dinosaur actually mean"), the bit of the brain that regulates pleasure & reward lit up like a mushy pink christmas tree.

In the same way that primary rewards like sex and food are pleasurable, curiosity delivers a similar hit of dopamine. What's even more interesting, is that the hippocampus (the bit that helps create memories) is also activated. Not only does curiosity make us feel good, it also helps us learn & retain more.

So whilst the result of curiosity for evolutionary purposes (learning where food, shelter, resources are) may be less tightly-coupled in our modern-age, the natural high still remains; Giving us all of the warm & fuzzies when someone or something piques our interest (and yep, that absolutely includes celebrity gossip, who will win the 'Great British Bake Off' & whether Jane from Marketing may or may not have had a nose-job).

BE MORE CURIOUS

We are all curious, but some are more curious than others.

As with most psychological traits curiosity has a genetic component to it. Some people will be born more curious because of who they are and who they come from.

But as always, personality traits are rarely entirely down to "nature", and the external conditions of someone's life can and do play a role. What's more, scientists are researching lots of factors that may impact curiosity - including stress, ageing & certain drugs that inhibit dopamine processing in the brain. In that sense curiosity can also be because of where someone is and where they came from.

Clearly then, being curious (or not) is not a static state. You can enhance your chance of finding something curious by doing things outside of your normal sphere of comfort, engaging with someone outside of your echo-chamber, or practising mindful listening. On the flip-side you can also suppress curiosity; by regime, by fear, and sometimes by ideology, which has the ability to neutralise the normal sensation of reward.

CHILD LIKE

A common question is whether we grow out of our curiosity. Enchantment, wonder and endless questions help a child to understand their environment, get their head around cause and effect, and learn how stuff works so they make fewer mistakes. As we get older and figure more stuff out (sometimes), this enchantment & wonder seems less useful. Fortunately, research suggests that whilst we may loose some of our diversive curiosity (our ability to be surprised), epistemic curiosity (our love of learning) appears pretty constant.

A huge reason for this is neoteny (ohh new word) - where as a species we retained a bunch of juvenile characteristics through to adulthood. Neoteny is an example of an evolutionary special offer, it's a package deal including relative hairlessness, having a big brain to body size ratio, and lifelong curiosity and playfulness.

And it's worked rather well. Where even in adulthood, when we're safe & warm, well-fed & have a family, we still retain the ability to be intrigued by new ways of doing things and new ways of thinking, allowing us to adapt & innovate... and giving us a little buzz in the process.

sources & further reading

How Curiosity Changes our Brain: https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2014/10/03/how-curiosity-changes-our-brains/?utm_term=.404f13a93f80

Curiosity Helps us Learn: https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2014/10/24/357811146/curiosity-it-may-have-killed-the-cat-but-it-helps-us-learn

Why? What Makes us Curious (2017) (available here): https://www.amazon.co.uk/Why-What-Makes-Us-Curious/dp/1476792097

Why Are We So Curious? http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20120618-why-are-we-so-curious

States of Curiosity (research paper): https://www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273%2814%2900804-6